In a recent personal project, I had a requirement to create a small web application that uses websockets which could be portable across different devices. The traditional structure I would take would generally involve using docker compose with the UI, database and backend services running in different containers. While this works for a traditional webapp stack, the requirements I had was more constrained. The application must be packaged into a single binary and be able to run across different platforms. In addition, it must also support the websocket protocol.

Eventually, I managed to create a single binary using golang and the embed directive which stores the migration files and UI asset within a single binary which are accessed when run.

This is inspired by the Vault binary which does something similar by embedding its UI contents into the CLI.

Process

The application is an example chatroom which allows you to create channels and converse in each of them. Each message is persisted to the database but also broadcast via websockets to each connected client. The original application was based on a tutorial from GoLand blog but I updated it to use websockets rather than using the original polling mechanism to render messages.

I adapted the chatroom example from gorilla websocket library by modifying the client structure to accept an additional parameter of a room ID:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

type Client struct {

roomID string

hub *Hub

conn *websocket.Conn

// buffered channel of outbound messages

send chan []byte

}

func ServeWS(hub *Hub, w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request) {

params := r.URL.Query()

key1 := params.Get("roomID")

log.Printf("REQUEST ID: %+v\n", key1)

conn, err := upgrader.Upgrade(w, r, nil)

if err != nil {

log.Println(err)

return

}

client := &Client{

roomID: key1,

hub: hub,

conn: conn,

send: make(chan []byte, 256),

}

client.hub.register <- client

go client.writePump()

go client.readPump()

}

The example uses the concept of a Client which serves as an interface between the incoming WS connection and a hub. The Hub consists of a struct which stores every client connection and broadcasts received messages to each connected client.

The Client struct has an additional field of roomID. This is retrieved from the ServeWS handler which registers every websocket connection of the format ws://localhost:8080?roomID=XXX.

The Hub maintains a map of every WS connection. The original example would broadcast to every client regardless of which room the user is in. To scope each message to only a specific channel, we need to create another struct to hold the roomID and data and modify the Hub struct:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

type wsmessage struct {

roomID string

data []byte

}

type Hub struct {

// registered clients

clients map[string]map[*Client]bool

// inbound messages from clients

broadcast chan *wsmessage

// register requests from clients

register chan *Client

// unregister requests from clients

unregister chan *Client

}

The original example used broadcast chan []byte which we have overwritten to support wsmessage which holds both the roomID and the actual data sent by the client.

When incoming data is received, it gets processed by a private readPump() function that creates a wsmessage struct that contains both the roomID and the message:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

func (c *Client) readPump() {

...

// original code from example

for {

_, message, err := c.conn.ReadMessage()

if err != nil {

if websocket.IsUnexpectedCloseError(err, websocket.CloseGoingAway, websocket.CloseAbnormalClosure) {

log.Printf("error: %v", err)

}

break

}

message = bytes.TrimSpace(bytes.Replace(message, newline, space, -1))

res := &wsmessage{

roomID: c.roomID,

data: message,

}

c.hub.broadcast <- res

}

}

The above wraps the incoming message into a wsmessage struct with the roomID from the Client and the message from the WS connection.

This is passed to the Hub broadcast channel which only sends the data to the clients associated with that roomID:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

func (h *Hub) Run() {

for {

select {

case message := <-h.broadcast:

room := h.clients[message.roomID]

if room != nil {

for client := range room {

select {

case client.send <- message.data:

default:

close(client.send)

delete(room, client)

}

}

if len(room) == 0 {

delete(h.clients, message.roomID)

}

}

case client := <-h.register:

room := h.clients[client.roomID]

if room == nil {

room = make(map[*Client]bool)

h.clients[client.roomID] = room

}

room[client] = true

}

}

}

The frontend UI is built using ReactJS. The WS is only enabled in the two components MessagePanel.js and MessageEntry.js. It uses the react-use-websocket library as it provides support for a single WS connection to be shared across components. Passing a WS socket to the components resulted in multiple WS connections being created. By using the library and setting the share: true attribute, this helps to solve the issue.

When a user enters a room, the previously created messages are fetched via the api endpoint from the application and rendered. It also initiate a websocket connection to the websocket endpoint, with its room ID as a parameter:

1

ws://127.0.0.1:8000/ws?roomID=<room ID>

This enables the messages to be scoped to a specific room rather than being broadcasted to all connected clients.

Another issue with the ReactJS application is the use of reacter-router-dom. During development mode, the UI is ran via a separate process. During deployment, after we bundled the JS and integrate it with the application, some of the routes would break as the browser assumes its trying to connect with one of the api backend routes, resulting in 404 errors.

To resolve this issue, we can implement a no route handler which renders the HTML template back, thereby fixing the routing issue:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

r := gin.Default()

r.NoRoute(func(c *gin.Context) {

log.Printf("%s doesn't exists, redirect on /\n", c.Request.URL.Path)

// Send index.html back for react router paths

c.File("chatui/prod/build/index.html")

})

By implementing the above, we are able to have routes that work for any environment.

Building and packaging

Using the embed directive in golang, we can bundle the UI and other setup files directly into the application. This can be a single file through the go:embed <filename> method which embeds and returns a single file as s string or bytes. We can also embed an entire directory using go:embed <dirname> format which returns an embed.FS type.

In our sample application, the following are used:

1

2

3

4

5

//go:embed chatui/prod

var server embed.FS

//go:embed database/schema.sql

var schemaSQL string

The UI is mounted as a directory in the server var. This is used by the gin-contrib/static library to serve the static assets under the root path:

1

2

3

r := gin.Default()

r.Use(static.Serve("/", static.EmbedFolder(server, "chatui/prod/build")))

The UI is bundled and built first under a separate directory of chatui/prod/build. The database schema file is used to run the initial migrations before the application starts.

By adopting the above techniques, I was able to recreate a single binary for a web application which is portable. To run we simply invoke the binary:

bin/chatapp

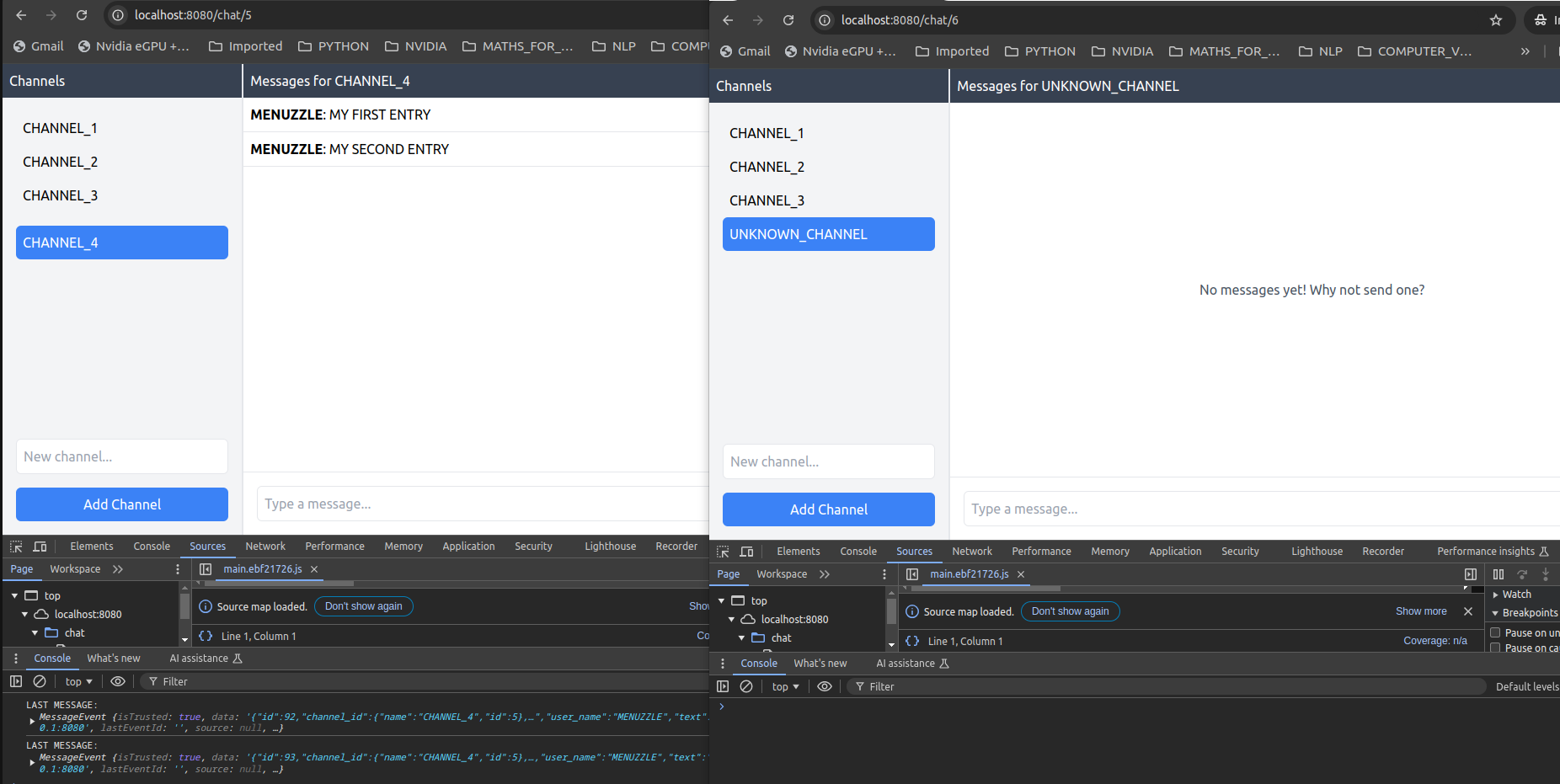

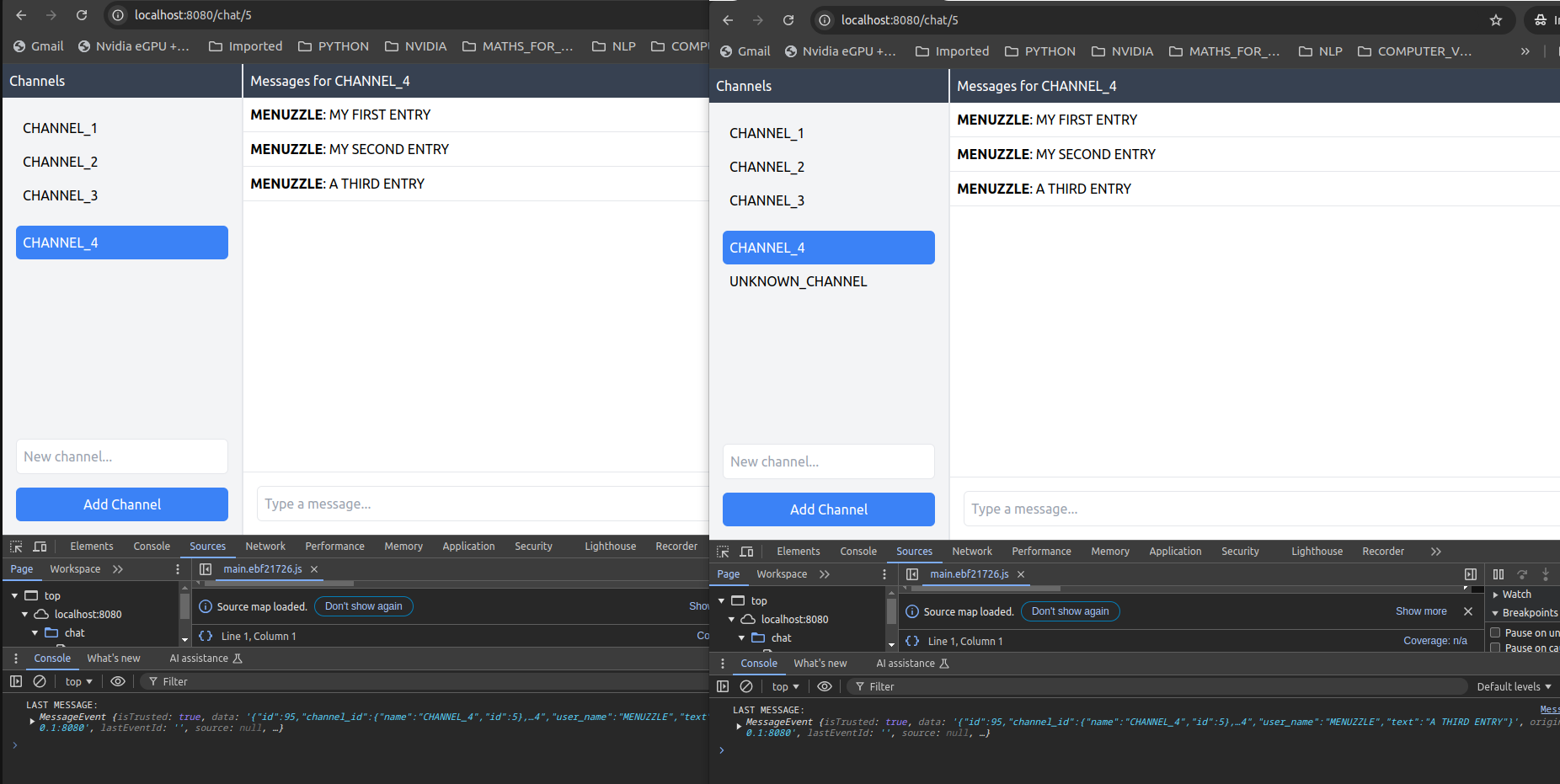

Below are some screenshots of the single application. The first screenshot shows how messages are only sent for each channel. The second channel shows the broadcast of messages in the same channel.

From a production perspective, I would probably use an embedded database rather than sqlite3. The UI also needs to be refactored so the websocket only gets created when a user enters a room.

In summary, this post highlights the use of go:embed directive its potential use. More details about it can be found on the golang embed directive webpage.

Example source code can be found here: https://github.com/cheeyeo/GOLANG_EMBED_EXAMPLE